A Deep Dive Into The Deep Core

When most people hear the word “core” they think of a six-pack. That six-pack muscle (the rectus abdominis) is ONLY the outer layer of your abdominal muscles, and I wouldn’t even really include that muscle in my definition of what the core is. Let’s first define the core, then we can get into what it does and how to train it.

The Deep Core Muscles

The Diaphragm

Picture a can of beans. The very top of the can is your diaphragm. It is the muscular lining that separates your chest from your abdomen. As you inhale, this dome-shaped muscle engages, which causes it to draw down and widen. When you exhale, the diaphragm relaxes causing it to narrow and lift back into its dome shape.

The Pelvic Floor

The very bottom of the can is the pelvic floor. It is a network of muscles that creates a sling from your pubic bone to your tail bone with attachment points on the sitz bones. I have an entire blog post about it here.

Note: The image to the right is of a female pelvic floor. All people have a pelvic floor, and while there are some anatomical differences between males and females, the role of the pelvic floor muscles in regulating pressure is the same.

The Transverse Abdominis (TVA)

This makes up the walls of the can. It is a corset-shaped muscle whose anatomical function is to compress your abdominal contents (this function plays a huge role – hold tight!). The TVA is the innermost layer of your abdominals.

The Importance of Abdominal Pressure

The three muscles listed above work as a team to manage pressure in the abdomen. You have a chest cavity, which holds your lungs and heart in your ribcage, and you have an abdominal/pelvic cavity (I’m going to refer to these two as one unit: the abdominal cavity), which house your guts and maybe a baby. The diaphragm separates these two cavities. The pressure in your chest cavity increases and decreases as you breathe – there is an increase in pressure as you inhale and a decrease as you exhale. The pressure in your abdominal cavity is affected by the movement of your diaphragm up and down as you breathe, AND it is affected by the tension/activation of your TVA. The pelvic floor has a smaller effect on intra-abdominal pressure than the TVA or diaphragm because it has a smaller range of motion, so its main role is to serve as the bottom support of the abdomen.

Why does abdominal pressure matter? As the TVA activates, it compresses your abdomen, which increases intra-abdominal pressure. This pressure is what stabilizes your trunk. Let’s go back to the can analogy - If the can is pressurized it is very sturdy. Once you open it, the pressure decreases and you can crush it with a single stomp. Without an appropriate amount of pressure in your abdomen, your ribcage would collapse down toward your pelvis.

Note: You may be wondering why I’m not including the outer layer of the abdominals in my definition of the deep core. If you’re a super anatomy-nerd you may also be wondering why I’ve left out the multifidus. The outer layers of your abdominals (the obliques and the rectus abdominis) reinforce the TVA, but they don’t play as much of a role in managing abdominal pressure changes as the TVA does. The same goes for the multifidus - while it does play a large role in trunk stability and is usually included in the definition of the core, it doesn’t regulate pressure like the diaphragm, TVA, and pelvic floor do, so I’ve excluded it from my definition here.

Deep Core Exercises

Now that we’ve shifted the conversation to the inner core rather than the outer abdominal muscles, you’re probably realizing that core exercises might not look like what you thought they would! A good starting place for core exercises is to practice movements that challenge your trunk stability. When your trunk stability or balance is challenged, your TVA will automatically kick in to generate pressure, keeping you in the position of your choosing (standing, squatting, face-up, all fours, etc).

I like to imagine that the body is a big web - think Vitruvian Man with a spiderweb layered overtop. The center of the web is at the navel. A spider sits right in the center of its web because from that place it can feel movements happening anywhere within it. Same goes for your “core” - movements at the far reaches of your limbs are felt in your trunk. You pick up your child? Your TVA engages to stabilize your torso as you stand up. You kick a ball? Your TVA turns on to stabilize your trunk providing your leg with a strong anchor for better leverage. You take a sharp corner while driving? Your TVA engages to keep you upright. Movements that seem like they aren’t “core exercises” can totally be core exercises.

Here are a few of my favorites (warning: you’ve seen them all before):

Bird Dog:

From an all-4s position, reach opposing limbs away from each other. The core muscles will activate to keep your torso still. You can check your form by ensuring that your shoulders are level, both front hip points are directed towards the ground, and you haven’t shifted your weight toward your supporting knee. I find that pressing down into the supporting arm allows me to find better activation in my core muscles - give it a try!

Progressions:

-Bottom Foot Hovered: Place a rolled mat or a yoga block under your knee so the bottom foot isn’t touching the ground.

-Knee Hovered: Press down through your supporting hand and toes to hover the supporting knee.

-From Plank: This one’s a doozy! From a plank reach your opposing limbs away from each other. Make sure to keep your torso square with the ground!

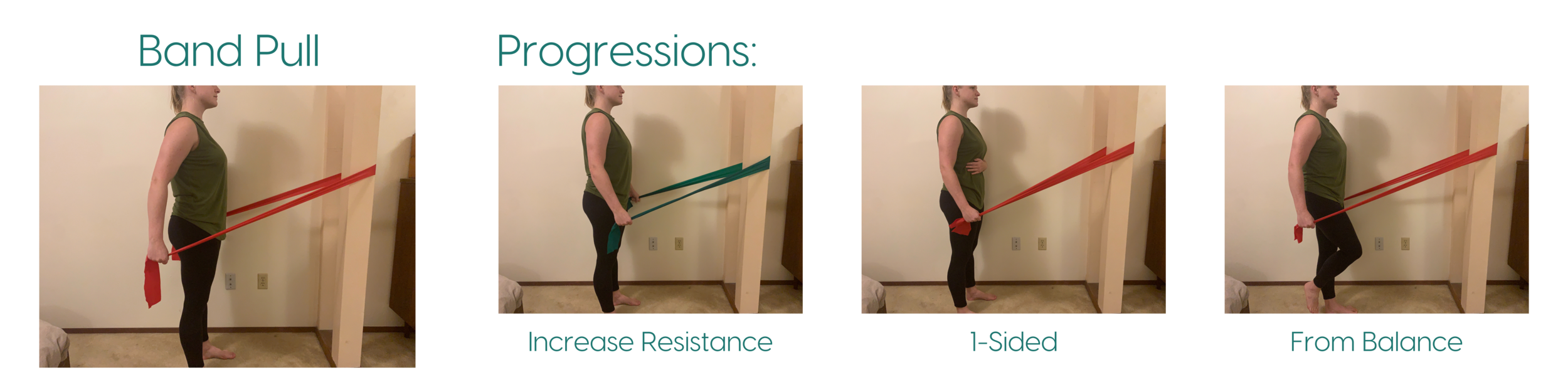

Band Pull: Stand tall with your head, ribcage, and pelvis stacked over your heels. With straight arms pull the two bands backward. As the resistance from the band increases, the work required by your body to stay upright increases. Your TVA should increase its activation in response to the increase in load.

Progressions:

-Increase Resistance: Choose a heavier band or stand farther from the anchor point.

-1-Sided: Place both ends of the band in a single hand. Be sure not to rotate your torso as you pull your arm back!

-From Balance: Standing on a single leg perform the exercise described in the original exercise.

A squat typically involves hinging at the hips, knees, and ankles. Core activation is required to stabilize the trunk when moving through the up and down movements of a squat.

Progressions:

-Increase Load: Hold a kettlebell or dumbbells at your chest, shoulders, or down by your sides like you’re picking up two suitcases.

-Asymmetrical Loading: Hold the weight on only one side of your body. Be sure not to lean toward or against the weight!

-Dynamic: Picking up your pace and jumping are great ways to increase the load on your core muscles.

Of course all of the exercises above involve many more muscles than just your diaphragm, TVA, and pelvic floor, but reframing them as core exercises highlights the fact that your core is involved in everything that you do.

One last thing I was to emphasize is that the core is a dynamic system. There isn’t a “core switch” in your brain with “on” and “off” labels. The muscles of the core work together to generate an appropriate amount of pressure for the task at hand. If you pick up a pencil the pressure generated in the core will be much smaller than if you pick up a refrigerator. Try to keep that in mind as you move through the progressions in the exercises above.

I recently asked the PROnatal Support Instagram community what they wanted to know about exercise during the perinatal journey and EVERYONE wanted to know what they were supposed to do for their core. This is the first post in a series of blog posts on the core, so stay tuned!!

If you’re eager to get moving, join one of the Pre or Postnatal Movement Classes!